Spotify announced a new exchange, SAX. Let’s see if that comports with our model.

Spotify and the “Logged-In Internet”

The nice people at Spotify invited me to an event in Chelsea last week to debut their new ad tech offerings. The thing that really struck me was meeting the man behind the AI DJ “X”, who is a real person named Xavier Jernigan.

Let’s get out of the way what was announced, since you’ve likely heard it already:

Ad exchange called “SAX”, integrated with $TTD ( ▲ 3.16% )

Support for UID2 and Ramp-Id from $RAMP ( ▲ 0.26% )

AI creative solutions

Updated ad manager

Good stuff, over all. What does this tell us about the state of the “open web” market, and the audio business in particular.

Welcome to the Logged-In Internet

I’ve written and spoken extensively about how the “open web” is becoming an increasingly poor framework for understanding how advertising is evolving. Spotify is now available for buyers via their favorite DSP, does that make them part of the “open web”?

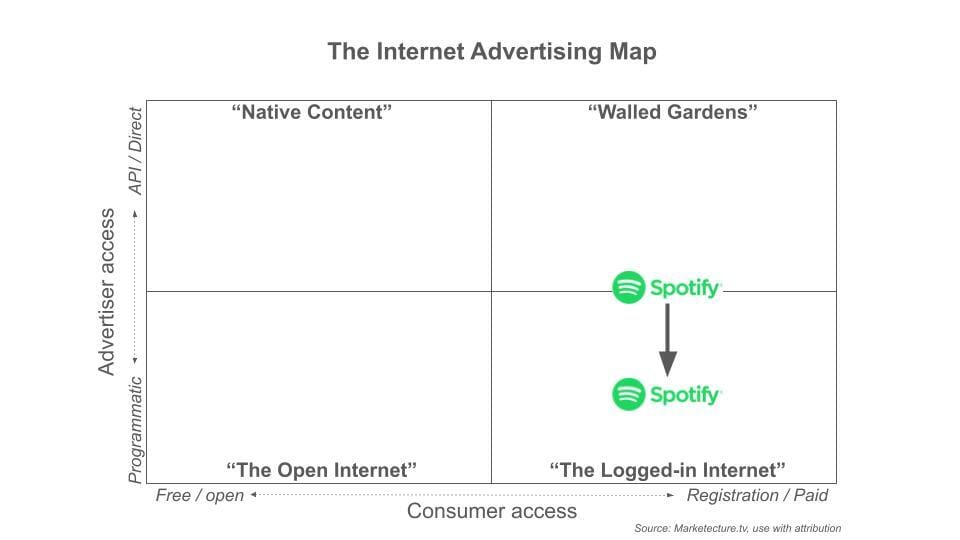

I have suggested an alternative framework where we characterize businesses by their openness to consumers against their openness to advertisers. (see article: What is the open web, anyway? ). I’ve reproduced the money-chart from that post if you don’t want to re-read:

With this week’s announcements Spotify moves from the upper-right(ish) corner, to the most advertiser-friendly bottom-right. In moving here they join Roku, most CTV companies, and premium news publishers.

From the perspective of programmatic advertising, the bottom-right is the most exciting place to be, as you enjoy a triple whammy of benefits:

Premium content (or else why would they login?)

Identity resolution

Spot buying

Control over technology / transparency (to some degree)

Ad Manager(s)

Another way to look at the vertical axis is about how high you have to go (vertically, not pharmaceutically) before you think building your own “ad manager” is a good idea. And conversely, how low you sink before you turn on the programmatic pipes. Famously, despite a flow of ~$500 million in revenue, Facebook shut down its open pipes to capitalize on its data and control. How should other companies evaluate the same decision? And how does a company like Amazon, that runs its own DSP like a “hedged garden” fit in?

To start, let’s get real. If you can make it work, you want to be in the upper right corner, running your own {X}AM, and capturing 100% of the value of your inventory. The fixed costs of engineering, etc are easily dwarfed by the benefits of having your own buying system, namely:

Keep 100% of every dollar

Ability to innovate

Not tied to open standards

Own the customer relationship

Avoid data leakage

Solution for advertisers of all sizes

You could even come up with a new 2×2 matrix, exploring which types of buying platforms are offered by different kinds of media companies. (look below, I did!) On the vertical axis we show companies that have their own ad manager vs programmatic, and on the horizontal axis we move from no investment in stand-alone ad tech to fully invested.

Source: Marketecture.tv

The upper-left corner is dominated by Meta, which abandoned any plans to either let its inventory get bought programmatically, or participate in the ad tech market. But interestingly, X, Spotify, and others have been edging away from the fully closed strategy and letting some bidding happen.

In the bottom-right corner you have what I call the “Open Innovators” — big companies that are investing in ad tech to build their businesses, as well as new areas of growth. Comcast’s “Universal Ads” is a new entry to the conversation.

And on the upper-right, if you both are fully committed to a closed strategy and also have your own ad tech tools, then you’re using your advantage to prey on the rest of the ecosystem. I’ve called these the “predator gardens”.

Some thoughts on audio and Spotify’s strategy

A couple of years ago I think Spotify’s strategy in advertising could probably be summed up as “lets be the Google of audio.” What that meant, more or less, was to buy or build the combination of platforms tools, along with an ad network, in order to get access to the most audio inventory and thus get the most advertiser demand. This is probably similar to how FreeWheel used to think of its strategy (“the Google of quality video”). The problem in audio is that — unlike in the fragmented web — the rest of the audio market was not going to rely on the platform of a competitor, and creators were going to be forced to multi-home.

In audio consumers are split between Spotify, Apple, and YouTube, making a dominant strategy impossible. The audio ad market is also not especially large, and the number of independent publishers to align with your platform is small.

Instead of a supply-focused strategy, Spotify seems to now be following a demand-driven strategy, which can be characterized simply as “make as much money as possible.” With the company’s scale in engineering they can invest in areas like AI creatives, strategic audio creative services, and the like, which can get them advertiser scale even if supply-side scale is a zero-sum game between the giants. While they may not be able to run the table like Google, establishing themselves as the largest, and best-monetized audio channel, will be a powerful position to hold.